Jöttnar Pro Team member Mike Pescod recounts a spooky ski descent of the Ebnefluh in Switzerland's Berner Oberland

You’d have thought a solo ascent of Les Droites in the Mont Blanc massif - or perhaps the first ascent of a route on an unclimbed face in Peru - would be at the top of the list of my favourite climbs. They are certainly on the list, but when I am asked about it, I usually say my best experience in the mountains was actually a ski descent. Skiing from the summit of the Ebnefluh (3,962m) and back down to the Hollandia Hutte in the Berner Oberland is usually a quick, stress-free ski. But when Mike and I did it, it could not have been more serious or more rewarding.

There was quite a build up to this one. We had a plan of spending two weeks in the Berner Oberland in February, skiing between huts, skiing a few peaks, and doing some climbs as well. The dates were fixed, so when we arrived in Visp to find the avalanche hazard to be high, we knew we would have to be cautious: the glaciers in the Berner Oberland are several kilometres across. We were concerned about avalanches reaching us in the centre of the glacier as we walked up to Konkordia.

With food for two weeks, plus ropes and climbing equipment, the ascent was tough going; we got to the Konkordia Hutte after dark, where we found a team of Dutch skiers with their guide after three days of being stuck in the hut due to the weather and avalanche forecast. We agreed it was pretty unpleasant outside, but Mike and I were used to Scottish conditions and carried on the next day up to the Hollandia Hutte.

We managed a climb on Sattlehorn after a rest day at the hut to allow the weather to settle down. Next up was a slightly more committing plan I had hatched to climb a 1000m TD route. I had the British Mountain Guides scheme very firmly in my sights, and this whole trip was designed around getting the few remaining pre-requirements I needed in my logbook: one more Grande Course was high on the list.

The tricky thing was finding one; and, even more tricky, was getting to it. The plan was to go up to Ebnefluh, leave the skis there and descend a ridge on its north side to get to the Rotal Hutte. Here we were to spend a rest day, before walking back up to the north face and climbing back up to the skis. Then we’d ski back down to the Hollandia Hutte where we had left a stash of food and gear.

As it turned out, the ski up and climb down to Rotal Hutte went perfectly smoothly. On the rest day we wanted no more snow fall, so that the walk back to the face without skis was not too hard wading through powder. Unfortunately, it snowed all day: we measured the depth of snow each hour with the tried and tested 'picnic bench test'. We also phoned for an updated weather forecast every couple of hours.

We had little choice anyway, since the descent from the hut down to Grindelwald was avalanche prone, impractical on foot and a very long way from our gear. Thankfully there was not much depth of fresh snow, and we got to the face easily the next morning. We enjoyed the climb, but that is all I remember of it.

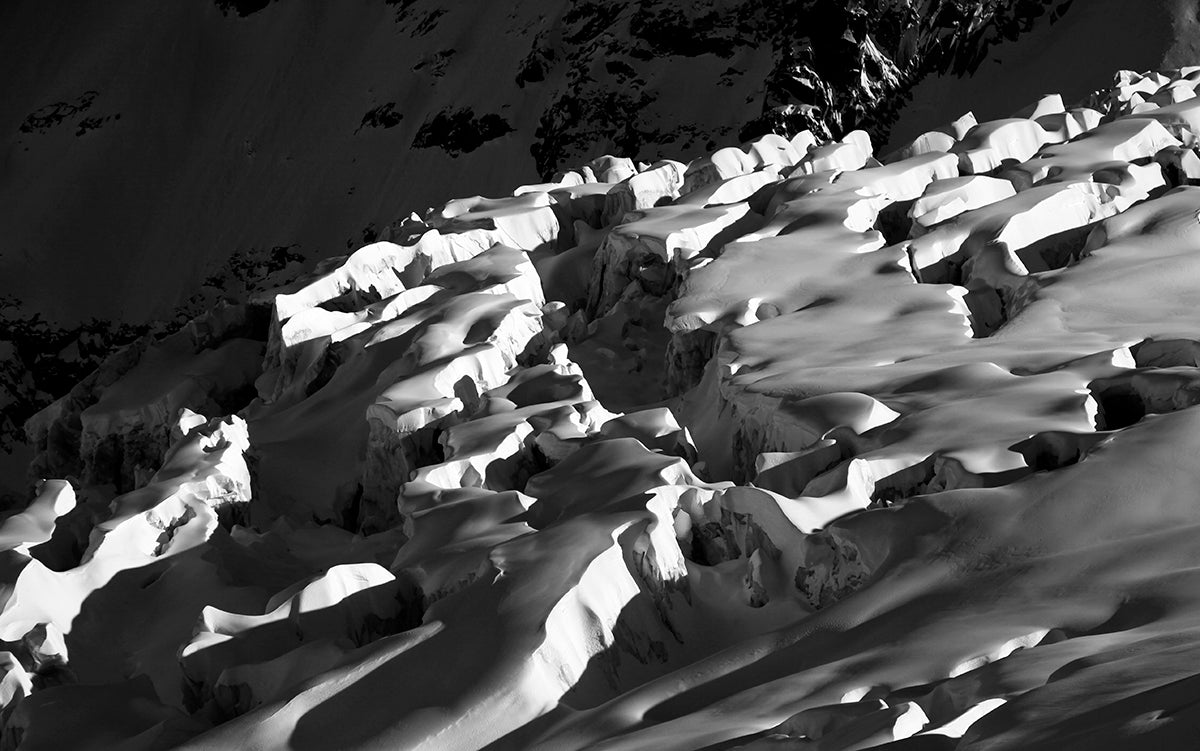

On top we found the skis still where we left them, but by now they were well encrusted in rime. The wind had blown for 36 hours and shifted a lot of snow onto the descent we now had to go down. On top of this, the navigation was going to be tricky in thick mist. The route was on gentle slopes, but the line curves continuously left all the way for the several kilometres to the Hollandia Hutte. Following a straight bearing was not an option, as there were seracs in the glacier to our left and avalanche-prone slopes up to our right.

"At one point, thirty metres ahead of me but invisible in the mist, Mike let out an involuntary cry, believing an avalanche had triggered"

We roped up with about 30m between us since we could not see anything at all in front of us. Mike went first, and I was in charge of navigating; both of us were trying to use a compass to keep us on the right bearing. We made very tentative progress, slower than walking pace, as we tried to evaluate the slope angle and snow texture in front of us.

Mike disappeared in the mist several times despite being only 30m away. At one point, he let out an involuntary cry and fell to the ground, believing an avalanche had triggered at his feet. Thankfully it was just a trick of the swirling snow around our skis.

The seriousness of the situation was clear. If we strayed off our route we would not find the hut in the kilometres of open glacier. Visibility was terrible, and the navigation very hard on skis. Travel on foot would have been impossible. We had no overnight gear with us, so we would not survive a night out on the glacier. From the hut down to the valley is several hours of skiing in good conditions; it would take a very long time in the conditions we were dealing with: we had to find the hut to survive.

"The seriousness of the situation was clear. If we strayed off our route, we would not find the hut in the kilometres of open glacier. And we had no overnight gear with us, so we would not survive a night out"

So, after a couple of hours of slow sliding, checking and rechecking our direction and location as best we could, reading vague contour lines, and trying to avoid the avalanche slopes, we got to a steepening. I reckoned we were on the last steep slope before reaching the hut. Everything added up: it felt right, it had to be right. As I glanced up, the mist cleared a little. And right there, less than 50m in front of us, I saw the hut.

Few moments in my life have given me such an overwhelming sense of relief and gratitude. We shouted, whooped and cheered. We laughed and celebrated as if we had just topped out on a major climb. The pressure and tension slipped away, and the previous hours we’d spent locked in absolute concentration disappeared. Many years of honing our navigation skills in Scottish blizzards had paid off at this moment.

That ski trip on the Ebnefluh pushed us to our limits. Success was definitely not guaranteed. In fact, any slight mistake or loss of concentration would have been disastrous. We knew this, and felt the weight of the situation, but just carried on calmly working on what we had to do. When we eventually found the hut, we knew that we had been utterly tested. Thankfully we passed the test, and went on to ski several more summits in the second week of our trip.

After all, mountain adventures are not just about the climbing or the skiing; it’s the whole experience that counts.

"Mountain adventures are not just about the climbing or the skiing; it’s the whole experience that counts"

Mike Pescod is a member of the Jöttnar Pro Team. You can find out more about him on the Pro Team page.