As the cutting wind whipped across the barren landscape, I skied south with my pulk dragging heavily behind me. The vast expanse of ice and snow stretched out before me, seemingly endless as I looked ahead and behind.

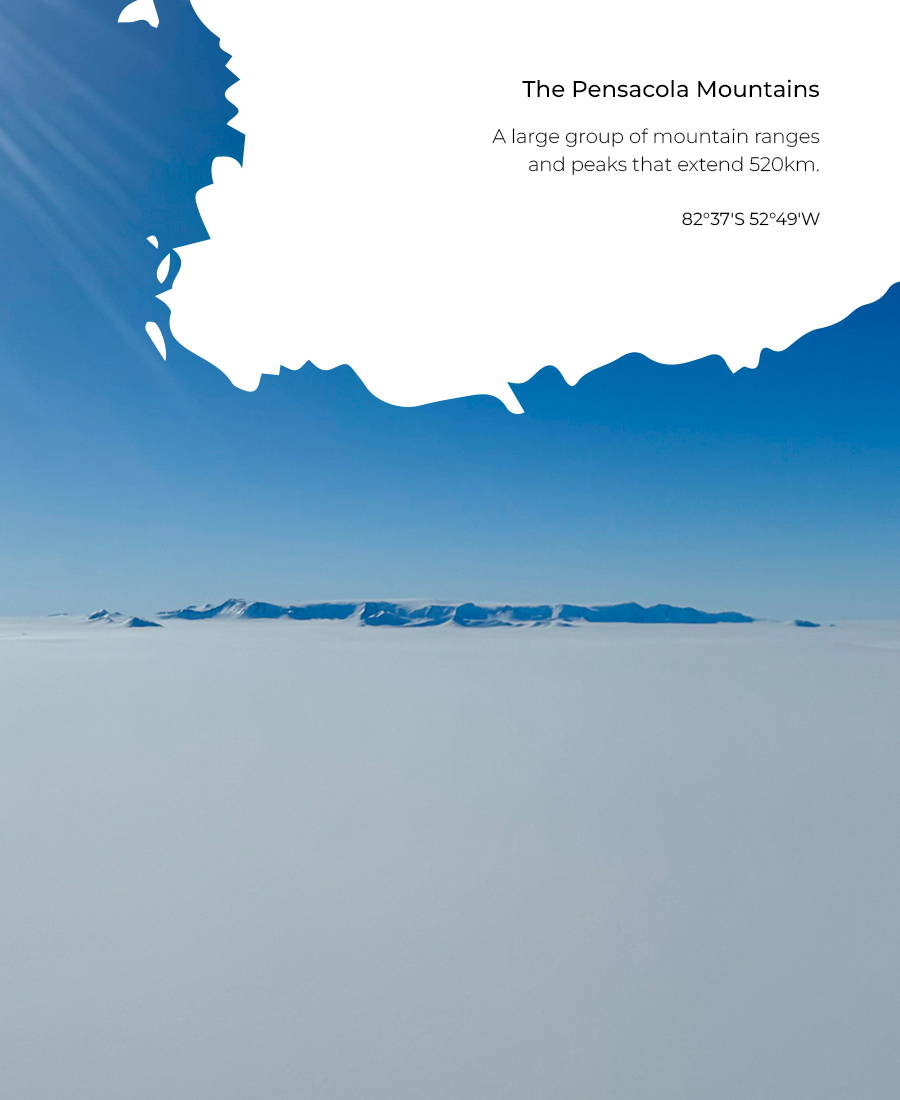

The Pensacola mountain range, through which I had toiled for the past 10 days, still loomed in the distance. It was day 31 of my solo unsupported Antarctic crossing. While I was enjoying the experience, the weight of the journey began to press down on me, both physically and emotionally.

Setting out on this expedition had been a dream of mine for years. Born of a Covid lockdown pipedream, the allure of Antarctica – with its untouched beauty, its extreme conditions, and the potential of complete isolation from the outside world – was the perfect mental and physical project I needed to focus myself while I was a part-time house cat.

"The Pensacola mountain range, through which I had toiled for the past 10 days, still loomed in the distance."

"The Pensacola mountain range, through which I had toiled for the past 10 days, still loomed in the distance."

Having a background of cold weather deployments in northern Norway from my 13 years in the Royal Marines, I spent the winters of 2022 and 2023 re-training and transforming my knowledge and experience. Moving from the military team-based routine into techniques and experience that suitable for a solo adventurer to tackle an Antarctic ski crossing. This took some gentle adjustments but nothing too drastic. With a history of applied resilience, both physically and mentally, I was prepared for the rigours of an 80-day traverse.

The challenge that faced me was a 2,000km crossing of Antarctica, beginning at the northern tip of Berkner Island and ending at the base of the Reedy Glacier via the South Pole. Laden with an optimistic 165kg of equipment and supplies from the outset. The journey would traverse vast stretches of ice and snow, spanning a frozen ocean, ascending a mountain range, and navigating hidden crevasses. Relying solely on what I carried with me coupled with my strength, resilience, and resourcefulness to conquer this formidable challenge.

However, pulling a pulk over featureless terrain in a hostile environment was a test of endurance like no other. In the beginning, each step forward was like pulling a full bathtub on a sandy beach with minimal glide. As the weight of the pulk attached to my harness dug into my shoulders, coupled with the daily ten hours of skiing, it didn’t take long for my body to ache.

Despite taking around 7,000 calories to eat each day, the hunger set in around day five as my body longed for further sustenance. Around day 10 I began to get strange cravings and for some reason, a fresh fruit salad and a can of Fanta were the ones that loitered longest in my mind.

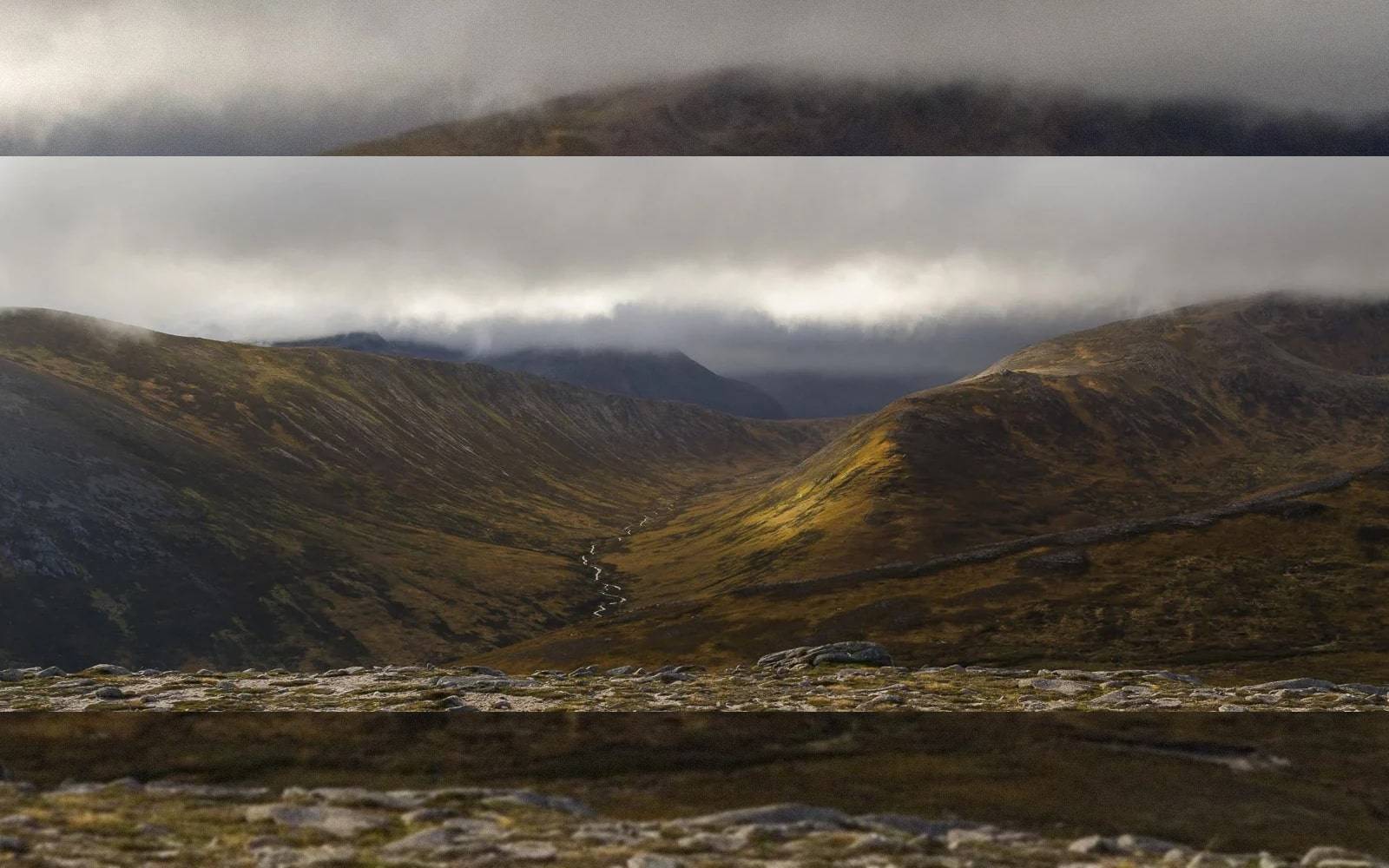

These cravings were only the beginning of the mental tricks my brain attempted to play on me. The landscape, often monotonous, was breathtaking yet occasionally overwhelming. One day nothing but glistening white ice and crisp blue sky stretching as far as the eye could see. I would feel so insignificant. The other it was total whiteouts. My visibility no further than one metre. Feeling totally lost and isolated.

Yet, amidst the vastness and solitude, there was a strange kind of beauty – a serenity that could only be found in the most remote corners of the earth. It is a sensation that since returning I have struggled to verbalise and probably always will.

Before I began, I knew that maintaining motivation and morale on a solo expedition like this would be essential. It’s all too easy to succumb to feelings of exhaustion, frustration, and doubt when confronted with the enormity of the seemingly insurmountable distance and terrain ahead of me. To prevent negativity from taking hold, which did occasionally creep in, I focused on small victories, breaking them down into weekly, daily, and even hourly achievements. These milestones, whether the treat of a podcast at the next rest stop, pitching my tent once I reached a certain time, or my weekly call home served as mini moments of triumph and aided in guiding my daily mental mindset.

However, avoiding the feelings of intimidation, fear, and loneliness was potentially the greatest challenge faced. The sheer scale of the 2,000km crossing was overwhelming when thought about in its entirety, and the emptiness of the continent was a constant reminder of my insignificance in this awe-inspiring place. Fear of failure lurked at some of the lonelier points. The whispering doubts and insecurities of whether I was capable of such a feat would often pop into my mind. Instead of letting the fear of isolation and inadequacy dictate my mental state, which would directly impact my journey, I wanted to embrace them as part of the experience. As a challenge to be overcome rather than an obstacle to be avoided or ignored.

Cheerfulness in the face of adversity is one tenet of the Commando Spirit, which is instilled during basic training. If you didn’t have this ability to make the bad seem good when at Commando Training Centre, you were going to struggle. This mindset is something that Commandos cultivate throughout their careers. On this trip, I had to dig deep into my cheerfulness reserve at points.

Some days were harder than others when the cold would bite deeper or the fields of sastrugi (waves of snow caused by the wind) were seemingly never-ending. In those situations, I reminded myself why I was there. Of the dream that brought me to Antarctica in the first place. The sense of accomplishment I achieved at the end of each day, which I would feel again once sat in my tent that evening. Who knew that 10 hours could pass so quickly yet could simultaneously go so slowly?

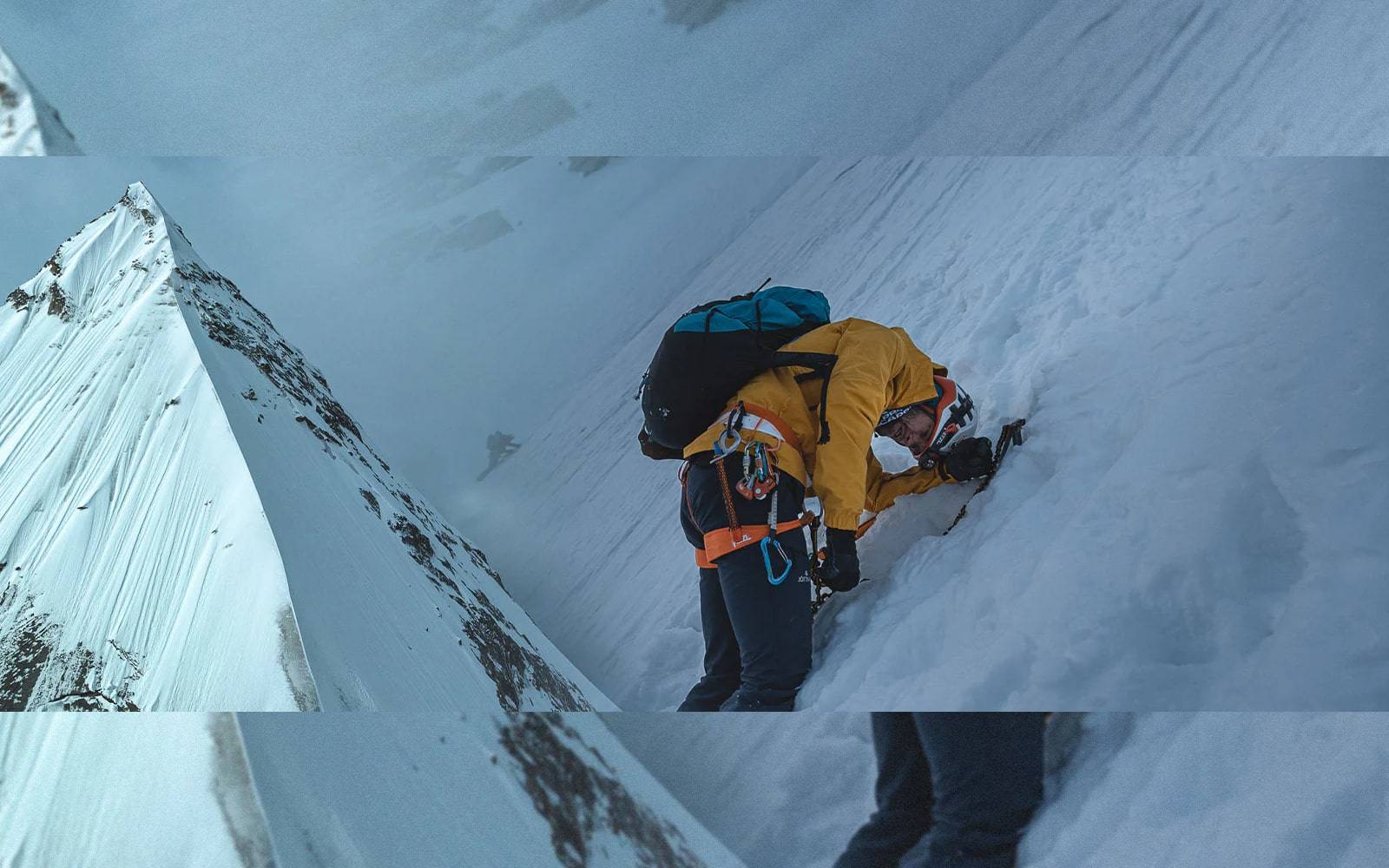

One vivid day that lingers in my memory: the 13-hour extravaganza of getting up into the mountains via the Wujek Ridge. A 300-metre climb that would not be amiss in an Alpine ski resort. This day required multiple lighter loads up and down the steepest section as it would have been impossible to do it in one shift. On my final trip down the slope leading my empty pulk to fetch the final few bags of food I took a hard fall. I was 12 hours in on an incredibly taxing day. All I could do was sit there. Drained physically and emotionally. I looked out at the view. I was overlooking stunning blue ice that led onto the vast Filchner-Ronne Ice Shelf. A vista that only a handful of people in history had ever seen – that put my situation into perspective. A time to dig deep into my cheerfulness reserve… ‘Cheerfulness in the face of adversity’.

And with that thought in my mind, I pushed forward, one step at a time, further south towards my goal.

The impact of time under fatigue began to influence my psyche and decision-making. As the days wore on, the relentless routine of skiing and disturbed sleep began to cloud my thoughts. Fatigue started to settle over me like a heavy blanket, weighing down my body and mind. Decision-making became increasingly drawn out and even simple choices required effort, willpower, and concentration.

I had trained for this, not only with my military background, but also while on specific expedition training trips in Sweden and Norway. I had specifically set out goals to establish a simple evening and morning routine that I could complete without too much thought. To help safely allow myself to enter a sort of autopilot when I was most drained. I’ve discussed in the past how in one training trip I had my tent up and down over 50 times in five days to ingrain this level of familiarity with this vital piece of equipment.

This repetition and knowledge of ability can, even in the depths of exhaustion, find internal strength and resilience that you would not know you possessed until placed in those situations.

Unfortunately, certain circumstances you cannot overcome with resilience, strength of mind, or a simple rest day in the tent. Earlier in the day I began urinating an unsettling amount of blood. A dangerous red flag that meant I must call the emergency doctors. They were not willing to allow the continuation of this journey.

On day 31 of this arduous Antarctic crossing, the incredibly tough choice was made to abort the expedition.

While I resented the decision at the time, I can see that this choice was borne out of necessity, as recognition that I have a young family waiting for me at home and the need to prioritise my long-term health and safety above all else.

Even with hindsight and some long sleepless nights back in the UK relentlessly self-examining my experiences, I have struggled to come to terms with what happened. The expedition was more than just a simple project. It was a passion, a distraction, a borderline obsession. It would not be an exaggeration to say that the majority of my free time and thoughts were dedicated to this expedition.

In the aftermath of returning from the seventh continent, I am left with a profound sense of gratitude – for the opportunity to experience the beauty and solitude of Antarctica, for the lessons I learned along the way, and for the internal reflection that this journey has afforded me.

I have revealed more to myself than I could have in any other circumstance. For in the solitude of Antarctica, I discovered a further strength in myself that I wasn’t aware of – a resilience, a determination, a sense of purpose that will stay with me. I am forever changed by this bewildering place.

I will return to this incredible continent that humbled me so greatly.

Sam Cox is a former Royal Marine and Polar explorer.